By 1850, Charles Finney had fully incorporated his three-stage

revival structure into the Sunday worship of the First Congregational Church in

Oberlin, Ohio. His "new measures" for revivals were already widely

known through his writings. Most American churches had no set structure or

liturgy for Sunday worship. Merging Sunday night revivals into Sunday morning

worship was an idea whose time had come.

By 1850, Charles Finney had fully incorporated his three-stage

revival structure into the Sunday worship of the First Congregational Church in

Oberlin, Ohio. His "new measures" for revivals were already widely

known through his writings. Most American churches had no set structure or

liturgy for Sunday worship. Merging Sunday night revivals into Sunday morning

worship was an idea whose time had come. Unlike Europe in this era, churches in America competed on a level

field, with none favored and none proscribed. The freedom to change, innovate,

adapt, and experiment was limited only by success or failure. As Nathan Hatch (The Democratization of American

Christianity) has explained, this climate produced an explosion of new methods

and movements unknown in Europe. Adapting the traditional "Service of the

Word" (see earlier post) into the three stages of Preliminaries into Sermon

into Harvest had undeniable appeal.

Unlike Europe in this era, churches in America competed on a level

field, with none favored and none proscribed. The freedom to change, innovate,

adapt, and experiment was limited only by success or failure. As Nathan Hatch (The Democratization of American

Christianity) has explained, this climate produced an explosion of new methods

and movements unknown in Europe. Adapting the traditional "Service of the

Word" (see earlier post) into the three stages of Preliminaries into Sermon

into Harvest had undeniable appeal.

The Revival Industry

By the early twentieth century, the only Christianity many experienced

was revivalistic Christianity. Hundreds upon hundreds of revivals, especially in

the summer months, crisscrossed America's cities and towns. They were just as

regular and widespread in the isolated churches of the Appalachian ridge or the

rural south. Many of these meetings were grand city-wide crusades, employing

celebrity preachers like Billy Sunday, Gypsy Smith, Aimee Semple McPherson, and

R. A. Torrey. These were supported by many different churches and organizations.

A far greater number, however, were operated by local churches, often tightly limited

within denominational boundaries.

To support these, music publishing companies poured out hundreds

of newly compiled camp-meeting songbooks with page after page of recently

written revival songs. From Blessed

Assurance to the newly composed Old

Rugged Cross, these were some of America's most popular songs for parlor

pianos and music boxes. It is no wonder the older hymns of praise that

had long dominated Sunday worship gave way to the bright gospel songs of Philip

Bliss and Fanny Crosby. By the end of World War Two, in thousands of

conservative Protestant churches, the only real difference between a revival

meeting and Sunday worship was when they occurred.

Revival Thinking

It cannot be a surprise, then, that fundamental assumptions

about worship also changed. The reason is obvious. Finney's structure and

methods for revival meetings were designed to produce decisions, what he called

"the Harvest." That's the whole point. By incorporating revival

music, revival sermons, and, above all, the revival practice of the invitation

time into the structure of Sunday worship, people are naturally going to absorb

revival thinking. Sunday morning's most important purpose must be decisions for

Christ.

"How many decisions did you have on Sunday?" is a

question every evangelical understands today that no one would have understood

in 1830.

How Does this Prostitute Worship?

I realize prostitute

is a strong word. Perhaps it is too strong. Because, I'm not suggesting what

has happened to Sunday worship is all bad. I enjoy Sunday worship and, as an

interim pastor in a small town church, I work within its traditional worship

structure. Ministry demands we love the church we have and take the time to

learn her story. As Eugene Peterson suggests in Practice Resurrection, ministers need to be careful because the

church we want can be the enemy of the church we have.

But, at a fundamental level, Finney's methods mean that

people understand and design Sunday worship with Finney's assumptions. After

decades of revivalistic Sunday worship, people accept as gospel – pardon the

pun – the most important single thing that can happen on a Sunday morning is for

someone to come forward and be saved. To criticize this is to potentially

forfeit your membership card in the Bible-believing Christian club.

The commitment of conservatives to evangelistic worship was

intensified by the polarizing divisions over liberalism in the twentieth

century. Liberal Christians were the

ones practicing what was labeled the Social

Gospel, while Conservative Christians believed in good old fashioned

soul-winning. You knew which were the Bible-believing churches in town because

they were the ones with gospel preaching and invitation hymns. Revival style

worship became the shibboleth of orthodoxy. And why not? Evangelism is

commanded. Congregational growth is surely a good thing. So, using worship for

the purpose of evangelism was more than simply effective. It was biblical.

You Cannot Serve Two Masters

There are some problems with this. One of these, of course, is

the realization that Finney's approach was new. From apostolic times to Finney

at Oberlin, the simple fact is Christian worship did not have a decision time

after the sermon. No one went to church on Sunday to "go forward." This

fact means, whatever they were doing in the process of evangelism, it didn't include using a Sunday worship invitation. The scripture and teaching portion of worship might, indeed, have people present in the process of learning of about Christianity (thus it was sometimes called the Service of the Catechumens). But, there was no invitation time and the unbaptized were not permitted to participate in (and perhaps not even be present at) the climactic Service of the Table.

Many biblically-informed Christians assure me that when they

lead or gather for worship, the main purpose is glorifying God. Certainly, the lyrics

of our popular praise songs seem to back up this assertion. This is what we

design the service to do. This is what it sounds like we are doing. Many times

this is what we tell ourselves we are doing. But, take a long hard look at

Sunday morning. There are some questions we need to ask.

Ultimately, Sunday worship cannot serve two equal goals, any

more than we can equally serve two masters. If it is designed primarily to draw

and reach unchurched people, then its primary target cannot be the already-churched

people. If it is designed primarily for worship, then it's primary goal cannot

be church growth. Evangelism or worship. Biblically and historically, gathering

for worship and going out for evangelism were two very different things.

Go with the Flow

So, if you aren't sure where the "this is the main point" was last Sunday, then follow through on

this simple experiment: Just ask yourself, "Where did Sunday worship this past week seem to flow?" Another way to say it is, "Where did the service seem to reach it's

climactic moment?"

You can usually tell where that moment-of-purpose fell in

the service by a simple observation. On

most Sundays, everything in the service

after this will feel a little like an epilogue or appendix. It's like everything starts winding down after

that. Look around this coming Sunday. When do you first see a few people

quietly start preparing to leave? When you see that, just back up a few moments.

Whatever was happening then, that's usually where the high-point of that

service was. Like the climax of a movie,

the high point of Sunday worship doesn't work early in the service. It does not

need to be the last thing. But, if it is too far back in the service, there's

that feeling the service reaches its high point and then begins to drag on and

on and on.

So, whatever was happening just before things started to

wind down is the first place to look for primary purpose. So, the question then

is, was that a moment primarily about insiders' worship or outsiders' decisions.

For many years, in the great majority of churches, that great moment was always

the invitation time after the sermon and before the benediction. In

the 1990s, when some churches eventually announced they would intentionally design

Sunday mornings for seekers, there was both insight and clarity: What many had long

structured as the primary purpose of Sunday worship, Willow Creek openly and

intentionally made their sole purpose.

This mindset, whether acknowledged openly or not, redefines worship

without necessarily changing its forms. What sounds like it is all about

worship is arranged and planned to also accomplish something else. That something else is tremendously

important. Reaching unchurched people – does anyone still call them lost? – is a

command our King has given us. But, it was

not the reason the church gathered as church for the apostles' doctrine,

fellowship, the breaking of bread, and prayer. In order to accomplish something

good, we find ourselves hijacking something even better. The second greatest

commandment supplanting the first great commandment in the priorities of the

church.

The greatest single danger of Finney's methods is that they work

so well. They do what they were designed to do. Finney did his homework. People

are drawn by excitement, moved by music, and touched by an engaging practical

sermon. Get the flow right and the sermon moving, especially at the end, and people

respond. Maybe not every week. But, by and large, it is the effectiveness of Finney's

approach to Sunday worship that makes it too attractive to abandon. We use

Sunday morning in the great cause of evangelism. And therein, as the Bard would

say, lies the rub.

A man who openly showers his wife with hugs and kisses and

gifts certainly looks like an example of a loving husband. A next door neighbor

who has taken his own wife for granted and whose marriage is doing downhill

might even see all this romance and be inspired to change. Maybe watching his

wife-loving neighbor saves this guy's marriage. That would be a good thing. After

all, who would not want to help a friend's marriage?

But, what if the romantic husband planned and carried out

his lovey-dovey actions with his neighbor's needs as a central thing in his

head? What if when a romantic time is done, the most important question was whether or not the neighbor was moved to change

his unromantic ways? It's a noble goal to help a friend's marriage.

But, to hold a woman's hand, gaze into her eyes and tell her

how much you love her in order to, at least in part, help your neighbor improve

his marriage is bizarre. Planning and carrying out words and acts of love in

order to accomplish something other than what those acts suggest is a charade. It

does not matter if he really loves his wife. What matters is what prompts his

choice of what he gives her, when he gives it, and what words he uses. Is it

for just for her or was it to help his neighbor?

Game Changers

The Word

Reframing Sunday worship as a means of church growth, as

Finney's model inevitably points, makes subtle changes to many things done in

worship. Everything before the sermon will serve the function of preliminaries.

Music will be used primarily to move the congregation from where they start to

where they need to be before the sermon. Long scripture readings will have long

since been jettisoned. Even if it were what the church needed to hear, it is certainly not what visitors want to hear. Unless you're careful, allowing

a variety of long passages might include unpleasant references to death or

pestilence or the threats of an angry God. Not what you want to have read aloud

if you have a lot of visitors that Sunday.

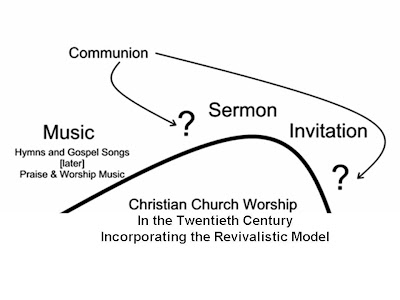

The Table

For some groups, such as the Christian Churches or Churches

of Christ of the Stone-Campbell Movement, the practice of weekly Communion

poses a special dilemma. For most American Protestants, adopting revivalistic

worship was simply a matter of adjusting what had always been the Service of

the Word portion of Christian worship. Communion had no place in Finney's

three-stage model for worship.

Christian Churches will respond to this in two approaches:

Communion will be placed before the sermon or it will come after the invitation

near the end of the service. This places the Eucharist as either part of the preliminaries

(often with music continuing right over top of it) or it hangs on as a kind of

slightly awkward appendix: We're just about done with worship, just hang on for

one more thing. And, so what had been done

weekly becomes simply done weakly.

By the twenty-first century, some church-growth committed

congregations rooted in the Stone-Campbell Movement will simply acknowledge the

Lord's Supper gets in the way of service flow and isn't of much interest to

visitors, anyway. Communion will simply be dropped from worship altogether. One

can appreciate the clarity and brutal pragmatism of the approach.

Evangelism

Maybe the most surprising result of Finney's model in

worship is how dramatically it has undermined evangelism. The very thing it

appears to promote it ultimately ruins. What people used to call witnessing has

now been politely redefined as inviting people to visit our church. "Do

you have a church home?" has replaced "Are you saved?" or

"Have you committed your life to Christ?" Evangelism has become what

the church does by building attractive buildings and hiring the most talented

speakers and musicians and then inviting people to come visit on Sunday.

One undeniable evidence of this is the language people use

when describing what might be called their conversion experience. In centuries

past, conversion might be described by saying, "My life was without God

and without hope until, in faith, I found salvation in Jesus." Now it is

far more common to hear, "My life with lonely and hopeless until I found

this wonderful and loving church." It is no wonder we speak of church

growth and the unchurched instead of evangelism and the lost. The entire locus of conversion has shifted under

the weight of Finney's revivalistic Sunday gatherings.

One amazing result is how rapidly and how large churches with

the right kind of Sunday gathering can grow. Growth driven by enthusiasm for

church needs no catechism or doctrinal education. It can be extraordinarily fast.

In communities with a broad evangelical base, any church that manages to foster

a great Sunday morning experience along with lots of friendly welcoming people

is going to grow at rates and to sizes churches years ago could not even

imagine. People who move from that city to another will look for a church with

a similar worship service. The name of the church or its doctrines, within

reason, are not that important.

Competition for top talent for the two central performers of

Sunday worship drives aggressive searches and salaries for these positions ever

upward. Instead of the sheep stealing of the 1800s (we are no longer those

narrow old Pharisees), we have replaced it with pastor stealing and worship

pastor stealing. "Have you met our worship pastor?" one Christian

Church elder proudly told me. "We stole him from Second Baptist in Dallas.

Doubled his salary." We have come to accept such boasts without shock or shame.

No one can question the effectiveness of Finney's model. Like I noted in the opening of this post, there is much good in this. Lives are changed. In several instances, churches long working within a strongly pragmatic framework have found themselves questioning their own measures of success. By and large, however, the appeals of rapid growth and ministry success continue to mute most questions and draw church leadership onward in the quest of bigger and better.

In a generation or two, I cannot help but wonder whether or not we will have demonstrated it is possible to be getting bigger and be disappearing at exactly the same time.

No one can question the effectiveness of Finney's model. Like I noted in the opening of this post, there is much good in this. Lives are changed. In several instances, churches long working within a strongly pragmatic framework have found themselves questioning their own measures of success. By and large, however, the appeals of rapid growth and ministry success continue to mute most questions and draw church leadership onward in the quest of bigger and better.

In a generation or two, I cannot help but wonder whether or not we will have demonstrated it is possible to be getting bigger and be disappearing at exactly the same time.

Don't Know if We're Coming or Going

Once there was a King who told His church to go out

into the world. Instead, they decided it would be better to just invite the world to come to church. That was pretty much the same thing.

6 comments:

Great series. Sad, but informative. The impact of Finney is pretty amazing and I would guess that most don't know his name, let alone his legacy.

Thank you for writing this series. I was familiar with some of it from reading the chapter on "Frontier Worship" in James F. White's book "Protestant Worship: Traditions in Transition". After discussing Finney, White is blunt on page 177, "Pragmatism has triumphed over biblicism," but didn't go into a much detail or layout precisely the effect on both worship and evangelism. Of course White was a Catholic looking from the outside in (as it were) and he was writing a survey with chapters on everyone from the Anglicans to the Quakers.

Thanks for so succienctly explaining yet another way in which evangelicalism is a cancerous perversion of Chrsitianity.

Lucy

Thanks for the post! One clarification to eliskimo: White was actually a faithful Methodist. He did teach liturgy at Notre Dame (among other places), and he seems to have been more of a "high-church Methodist," but he wasn't Catholic. FWIW.

Who ruined the model of worship that King David instituted? What was it's climax? Where did he get his ideas, and is his model the pure and holy model? If we brought it back what would it look like, and how would it incorporate Christ, or how did Christ make it so that David's model could be restored? Or is all that a type idol (model) worship instead of what interaction with God looked like in the Garden of Eden? Afterall, the end of Revelation is the restoration of the Garden of Eden. Can we have that model now?

Great writing. Thorough analysis. Thank you for this service to me.

Post a Comment