In 1830 the city of Rochester, New York, was rocked by week after week of spectacular revival meetings. These meetings would catapult the already well-known Charles G. Finney to national attention. Finney had been preaching periodic revivals for more than five years, but it will be the meetings at Rochester, extending well into 1831, that will make his name synonymous with American revivalism.

Finney insisted he was faithful to

Jonathan Edwards' version of Reformed theology. In time, though, his friends and

his critics agree his emphasis on individual responsibility for repentance placed

freewill in Arminian rather than Calvinistic terms. Finney's theology continues

to be hotly debated, particularly with the resurgence of Calvinism associated

with Piper, Sproul, Carson, and the Gospel Coalition. And, while Finney's

theology impacts his methods, this post will introduce the practical changes

Finney will bring into Sunday worship. These changes will impact churches in

both Reformed and Arminian traditions.

The Anxious Bench

During the extended meetings in

Rochester, Finney introduced a new practice in revivals that was both

controversial at the time, and will ultimately play a key role in changing

Sunday worship. He came to believe people who felt the need to repent and seek

God should be asked to do something. Prior to this, whatever people did in

revivals was more or less spontaneous and not limited to the end of a sermon. Finney

felt that it was in the final minutes of a gospel sermon many came to the very

edge of repentance, but hesitated and waited. That hesitation often allowed the

burning desire of repentance to ebb and cool.

In response to this, Finney's first

idea was to conclude the sermon by asking those who wanted to repent to stand

up. The results were encouraging. Some stood. Others, seeing some standing,

then also stood. He could see the presence of others standing was a great

encouragement to the hesitant. It was not long before the idea of standing gave

birth to the idea of asking people to come forward. A special front bench was

reserved for this, remaining visibly empty throughout the service until the

ending of the sermon.

If the sight of people standing

encouraged some, the sight of people actually leaving their seats and walking

forward was dramatically more effective. The movement and gathering of people

in the front naturally encouraged more unrestrained emotions. Their open

weeping and shouted prayers, heard throughout the crowd, brought forth many others

to walk, and sometimes run, forward to join them.

Never before in all church history

had a sermon concluded by asking people who needed to repent or seek salvation

to come forward. And now it was an intentionally planned moment in the meeting.

The entire sermon was geared toward this concluding appeal. Under Finney's

guidance, the entire revival service will be structured and designed with this

same climactic goal: sinners coming forward to receive Christ.

The "New Measures"

Like his role model, Jonathan

Edwards, Charles Finney carefully studied revivals. Unlike Edwards, though,

Finney's study was less to understand revival theology than to understand just when

and how revival occurred. This led him to design a structure in which revival

would dependably occur. Like the farmer who learned how to plow, when and how

to plant, how to weed and water with the confidence that, having done those

things, God will always provide the harvest, Finney believed planting the Word

of God in revival could be just as confidently planned and its outcome

predicted.

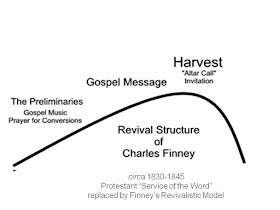

Finney's conclusions for an

effective revival can be simplified (my apologies to those who know how much complexity

I am glossing over here) into three connected stages: The Preliminaries; The

Message; The Harvest.

The Preliminaries

For Charles Finney, the

preliminaries were all the things in the meeting that lay the groundwork for

people to hear the sermon. The most important of these was music. Finney was a

good musician and had played the cello as a young man. He believed that good

music could move the heart and touch the emotions. The role of music was to do

just that. In that role, Finney favored songs that gave testimony to how

terrible was sin, how glorious was salvation, and how earnestly the love of God

calls out to every human heart.

Although Finney did not discuss

music in his lectures on revival, he clearly made great use of it in his

meetings. He employed a choir and brought Thomas Hastings with him as a musical

assistant. Hastings compiled songbooks and wrote the hymn melody most Americans

associate with Rock of Ages. Music

served as a way to draw people to the meetings and then to prepare them to be

spiritually and emotionally ready for the sermon. As D. L. Moody and Ira Sankey

will demonstrate 50 years later, uplifting and sentimental revival music is so

critical that every great revival meeting needs a music leader as much as a

preacher.

The Message

Revival sermons focus on the great

themes and stories of the gospel. The wrath of God deserved. The love of God

offered. The Prodigal returning home. The prayer from the cross in which the

Savior offers forgiveness toward those who have up to that point rejected him. These

powerful themes and passages were joined with dramatic descriptions of hell and

of heaven. Stories of a wayward sinner's mother faithfully praying night after

night for her sinner son to repent tore at the heart strings of grown men in

this highly sentimental culture.

Finally, the sermon would turn

toward a great call, a glorious appeal, for the Prodigals to return and for

sinners to answer their mothers' prayers. People would, of course, know there

was a place down front where those deeply moved and touched by the Spirit of

God would be invited to come. The faithful listened in those final moments and silently prayed for the time of harvest they knew was coming.

Finally, the sermon ends with a

great call for all those far away to come home. And, to come home by coming

down. There is no actual evidence of a formal "invitation hymn" in

the 1830s (as there will clearly be later), but it is reasonable to assume

music was employed. In any case, we know dozens, often hundreds, would come

forward at Finney's revivals. They would sit or kneel and pray for God's grace.

Often, retaining at least an outward framework of Calvinism, they would plead

for God to remember them. That is, to have included them within the predestined

elect. The incongruency of a man tearfully pleading with God to have, since

before creation, unconditionally included him within the number of the elect, is

typical of the tension between Calvinism and revivalism.

Sunday Worship in Oberlin

What happens in the Sunday worship at the First Congregational Church in Oberlin is as understandable

as it is revolutionary. Charles Finney simply brings his three-stage structure

for a revival meeting and incorporates it into weekly Sunday worship.

To understand how easily this

occurs, you need to recall what I shared in the previous post about Finney, Sola Scriptura. The church in Oberlin,

like most American churches, already approached Sunday worship as the Service of

the Word, alone. Scripture reading, music, prayer, and preaching were already

the normal fare for Sunday worship.

The difference was that Sunday

worship was, up to then, approached as a gathering of the church. Scripture

readings could be quite lengthy. Sermons were addressed to believers, with

their purpose being to strengthen and deepen people who had long identified

themselves as Christians. The music of worship was music believers addressed to

God in terms of worship. O Come All Ye

Faithful presumed those singing were already faithful. All Hail the Power of Jesus' Name presumed those singing were the

saved already joining the sacred throng

and prostrate angels in worship.

The difference was that Sunday

worship was, up to then, approached as a gathering of the church. Scripture

readings could be quite lengthy. Sermons were addressed to believers, with

their purpose being to strengthen and deepen people who had long identified

themselves as Christians. The music of worship was music believers addressed to

God in terms of worship. O Come All Ye

Faithful presumed those singing were already faithful. All Hail the Power of Jesus' Name presumed those singing were the

saved already joining the sacred throng

and prostrate angels in worship.

In the Sunday worship Charles Finney will

introduce in the 1840s, the assumed purpose of Sunday worship in the minds of people

does not change overnight. It is likely Finney, himself, does not abandon that

assumption. He is merely changing a few details of procedure. But, in very powerful ways, how we practice worship will, over time, influence what we think about worship.

What he does might be presented as simplifying

Sunday worship. Oh, and this simplified structure also tends to reward the

church that adopts it with increased numbers of decisions (or prayerful

appeals). There are some other changes, too. Extended scripture readings will need

to be gradually reduced and then abandoned. Those planning and leading music

will begin to see its role as, at least partly, preparing people for the

sermon. And, just as in the revival, the high point of the service will

increasingly feel like the conclusion of the sermon and any responses that

follow.

By 1900, a large number of churches

with strong links to revivals, Methodists, Baptists, and many others, will have

naturally adopted Finney's revival structure for Sunday worship. Music written

for revivals will be added into Sunday worship, gradually replacing older

hymns. By 1950, especially among groups that resisted theological liberalism, Finney's

three-stage structure in Sunday worship will be everywhere. A person could visit

a Methodist church one Sunday, a Baptist church the next, a Nazarene church the

next and then a Christian church: all of them would have the same basic

structure (preliminaries into sermon into invitation), the same revival congregational

music sung, and sermons on gospel themes all ending with what might be exactly

the same invitation hymn, Just As I Am.

In the next and final post of this

series, we will finally address head-on the statement that has run throughout

the titles of these posts: How Charles Finney ruined Sunday Worship. And, I

will return to a statement made in the introductory post. I believe these

changes have both prostituted worship and undermined evangelism by redefining

both.

Thank you for boldly and fairly examining Finney's influence on the life of the church. Over a hundred years of pragmatism have caused us to assume that our contemporary worship practices are in essence the same as those of the New Testament church - or at least those of Brother Campbell.

ReplyDeleteI'm looking forward to your third installment.

I have enjoyed the first three episodes (intro and parts 1 and 2) and am looking forward to the next one.

ReplyDelete